About

Moth Minds is an upcoming platform for grant patronage, a new way for individuals to support inspired individuals through bespoke funding schemes. The platform will help you set up and run your own grant programs — or perhaps help you to contribute to collective efforts.

This piece is my take on the platform announcement: questions, thoughts, and things I would like to see.

Introduction

Moth Minds is an upcoming platform for grant programs.

Announced towards the end of 2021 — and still pending many details — Moth Minds is an enterprising response to inefficiencies and fragmentation in the independent research and creative works grant funding space.

More concretely, the platform presents itself as a service that helps individuals (and perhaps other entities) easily set up and administer their own grant programmes. Moth Minds is a tool for grant patronage schemes.

Moth Minds founder, designer-researcher Molly Mielke (@mollyfmielke), outlines her vision for the grant platform in a short manifesto on the project site. MM by MM.

This piece is my personal take on the upcoming platform, things I would like to see, comments on related challenges and opportunities, and some thoughts on the kind of grant program that I would like to run or participate in.

To be clear, I have no affiliation with Moth Minds — this piece is all speculation. I'm hopeful that I'm not completely off-target, but Mielke could well be aiming in an entirely different direction. Indeed, this piece can be read as a call for more clarity on the details.

Moth Minds

Moth Minds builds on a long tradition of the audience directly supporting their favourite artists.

A grant is a vehicle for supporting researchers, writers, artists, makers, and more. All kinds of thinkers and doers could be on the receiving — and giving — end of personal patronage. The goal is to encourage enlightened ecosystems.

For Mielke, "Moths" are people who choose to do their own thing instead of fitting neatly into some existing niche. "Butterflies", in contrast, seek to thrive in the environments they discover. Moths are the modernists who make the world anew, while butterflies embrace tradition and flourish within established boundaries.

In her introductory essay, Mielke argues that moths and butterflies are driven by different things. Butterflies rely on ambition to guide them to success in a world created by others. Moths on the other hand are motivated by an innate agency, a desire to pursue their own interests and realise a different kind of world.

This moth-butterfly dichotomy illustrates the need for this new enterprise. We are desperately short of moth vibes in our society. We are missing out on some of this great aggregate agency that drives the development of new things.

So how can we nurture and promote this positive agency in people? This is the central question that Mielke wants to tackle with Moth Minds. The starting point is a three stage process for boosting agency: the hook, the catalyst, and the sustainer.

The first step (the hook) is a good story, a narrative that outlines at a personal level how something in the world could be meaningfully different. The second step (the catalyst) is about convincing others of your story, to show them that a different kind of world really is possible. If you can validate your idea, if people believe in the story enough to give you their resources and support, then you can pursue the idea and try to make it a reality.

The third and final step (the sustainer) is about participating in a community. Agency is a shared concern, a collective effort. Individual agency feeds from and is constrained by the operational environment, the cultural milieu. New things don't exist in a vacuum. At the same time old systems may simply reject newcomers and their novelties.

Moth Minds is a platform that helps people take these three steps.

"Creating new resources to catalyze agency was the inspiration behind Moth Minds."

As far as I can tell, the point is not so much the development of any particular output in pursuit of increased agency. While new, shiny things can be nice, the objective really is more about increasing the overall level of agency in communities, raising the baseline for each niche. The thinking goes that as a society, we'll eventually be better off, if more people are empowered and activated to pursue a new world instead of simply seeking success in the old one.

And it's not really butterflies versus moths either. Mielke is advocating for more of a symbiotic scheme, where butterflies can support moths in their pursuit and vice versa. The new world is never centrally planned for the future, but rather emerges out of a thousand little individual decisions — small acts of grace — done along the way.

Mielke and collaborators are still figuring out the details, but the general idea seems to be that Moth Minds is a service, a software foundation, that helps individuals and perhaps institutions fund work towards a future they would like to see. This is done through the instrument of grant programs, smallish scale funding schemes, with the platform itself as the coordination hub. The platform will likely provide tools and resources for presenting and discovering "hooks" and "catalysts", and will also serve as a home or homes for the "sustainer" communities.

As it stands, the moth funding grant market is ineffective and wasteful, Mielke argues. A central location and process standardisation could unlock more grants, as funders and grantees could more easily find one another and agree on terms. This increase in grants, if supported by a receptive community, could then result in a greater impact overall, and ultimately a brighter future.

"Moth Minds allows you to invest directly in people that reflect a future you believe in."

Background

A brief introduction to platforms and a high altitude flight across the grant funding landscape.

Platforms 101

In modern socioeconomic parlance a platform can mean a few different things. Indeed, part of the charm of the term is its ambiguity and open-endedness.

The word 'platform' can refer to at least the following:

- A transactional system, a marketplace, that connects supply streams with demand,

- A technological framework, a foundation on which new products and services can be built,

- A matchmaking service, a kind of a registry for connecting people with one another and with other entities,

- A library, where users can discover and access a curated catalogue of professionally produced content,

- A publishing scheme, where users can themselves contribute to the library,

- A collaborative toolspace, where groups of people can work together on content, either in private or in public,

- A social space, where individuals can express themselves and interact with others in a variety of ways.

These descriptions overlap, and many of the most successful platforms support multiple ways of participation. Successful platforms often become veritable communities and can give rise to nuanced ecosystems around them, each with their own complex dynamics and behavioural patterns. All platforms are made up of people, and the greatest platforms reflect the richness of our lives and the cultural context of those participating.

At the end of the day, platforms are mediators. Sometimes platforms are the medium itself. Platforms connect supply and demand, producers and consumers, content and attention. They are the trusted middle party, the market maker, the arbiter, and the referee.

Through this neutral or de facto authority role, a platform can establish a common language for all proceedings, and build shared abstractions and understanding. Platforms establish norms around common interactions, for example through standardised contracts and units of transfer. Many platforms set standards for quality of service, provide feedback mechanisms for all parties, and in the broadest sense enable service and product discovery.

The motivation for these standardisation and abstraction efforts is efficiency. When everybody plays by the same set of rules, lots of protocol negotiation and other overhead can be skipped. More concretely, platforms seek to provide a better service and overall experience to consumer-users, than what is available through direct bilateral relations. For the producer, the platform presents an opportunity to access a wider market and an incentive to operate at a greater scale. For the collaborator, the platform is the primary locus of shared activity.

A platform can succeed only if it adds real or at least perceived value to the proceedings. If you build it, they may come — but the participants won't stick around if they get no value out of using the platform. Indeed, ALL market participants, whether or not producing or consuming, have to be better off using the platform, or it won't succeed. It's not enough that just somebody wins. In a platform game, everybody must win.

The flip side is that once everybody has even a tiny benefit, the platform can grow rapidly through network effects and compounding. Conversely, the way to kill a platform is to reduce the payoff, the delivered value, to the point where participation is no longer worth the effort. The platforms that go the distance have something to offer for the absolute beginner as well as the seasoned veteran. The user experience is key.

Finally, platforms have an impact beyond their own context. Platform users interact with their local environment and the rest of society. With the modern rent-seeking economy, platforms can help resource owners in dysfunctional markets profit from access to assets they are willing and able to hold — without adding any value into the system. This is corrosive from a socioeconomic point of view. On the other hand, platforms can connect people and ideas and resources together in a way that would not happen otherwise, resulting in novel socioeconomic activity.

In short, platforms accelerate and supercharge the markets in which they operate.

"Building and managing platforms is extremely difficult, and extremely rewarding."

Your Grant Here

Today, many institutions fund research and projects in their chosen fields through different kinds of grant schemes. Many of these efforts operate in isolation and require a considerable amount of navigation from the applicants. Grant programs often reinvent the wheel on the operational side and insist on specific rituals to be carried out on the altar of accountability. Many programs suffer from poor visibility, while others fail to connect with their intended audience.

Meanwhile, on the Web, things are a quite different. The desire to connect with others doing interesting things has resulted in a widespread donation praxis on the Internet. Relative strangers give money (or platform tokens) directly to each other as a form of personal endorsement, a combination of gratitude, encouragement, and advance payment for more of the same content. Communities form organically around prolific individuals and niche interests.

Online, everything is done in public — or at least everything has a prominent public element to it. Joining a community is easy, trying things out is easy, sharing is easy. All the platforms are carefully designed to be easy to navigate. There's always operational variety and some friction, but generally platforms do what they can to help authors and audiences play their part. There's so much visibility to go around, normal operations frequently go viral or escalate into drama. Platforms generate complex crowd behaviours with real world consequences.

The Web is the meta-platform on which we hoist the things we make and wish others to see, where we share things we find interesting or entertaining, where we play, and where we desperately try to connect with our fellow humans.

For some, online contributions already sum up to a kind of a grant in aggregate. People are empowered to pursue their own interests in service of an appreciative audience. At the same time, these one-person schemes often leave the works and the memes and the ideas isolated. These author communities spread and scatter all over the Web.

More broadly, the nature of work itself is evolving, with various kinds of digital jobs and creative pursuits leading the way. The pandemic accelerated a trend towards more dynamic, flexible, project-oriented careers. New ways of working have been developed over the years to challenge and complement the corporate-institutional model. More and more people are interested in the independent researcher path, the way of the freelance knowledge worker.

In a nutshell, there's a bunch of people keen to support their favourite artists and makers and researchers, and there's another bunch of people interested in meeting that demand by producing Great Stuff. Many probably wish to have it both ways, to be part of a community of sharing and appreciating. Unfortunately, there's friction in all this, and as a result of this inefficiency, we may all be missing out on some of the finest fruits of human ingenuity.

Some snapshots of the current landscape, with an eye towards representing the variety:

Platforms

-

Patreon (2013-) is a monthly membership platform for fans of individuals doing creative work, including independent researchers

-

Kickstarter (2009-) is a crowdfunding platform for creative projects

-

IndieGoGo (2007-) is a crowdfunding platform for gadgets, creative projects, and community initiatives

-

GoFundMe (2010-) is a crowdfunding platform for social and charitable causes

-

Experiment.com (previously Microryza, 2012-), is a crowdfunding platform for science projects

-

Gratipay (previously GitTip, 2012-2017) was a "tip jar for Github", a way to make small donations to open source software developers; Liberapay is the spiritual successor

-

GitHub (2008-) released their own Sponsors system in 2019, alongside developments such as the Core Infrastructure initiative and the npm-fund mechanism, all of which seek to support open source software development

-

Gitcoin (2021-) is another platform for supporting the development of open source software and digital public goods; the Gitcoin grant scheme is powered by quadratic funding, a donation matching system that favours broadly supported initiatives

-

Ko-fi (2012-) is a platform for one-off donations, crowdfunding, and other direct payment traffic

-

Kiva (2005-) is a crowdfunded non-profit lending platform for low-income entrepreneurs, a pioneering online microfinance scheme; Grameen Bank is another microfinance success story

-

Open Collective (2014-) is a transparency-focused money management platform for loose collectives, popular with smaller open source projects; see also their fresh take on co-operative ownership, Exit to Community

Grants

-

Fast Grants by Emergent Ventures — a response to the COVID-19 pandemic inspired by the speedy funding review process of the WWII era National Defence Research Committee.

-

The Fast Grants gang recently launched Arc Institute for funding "curiosity-driven biomedical science and technology"

-

Impetus Grants by Martin Boch Jensen (@MartinBJensen) and collaborators — for longevity research (h/t @ArtirKel)

-

MacArthur Foundation runs a prestigious fellowship program, funding individuals through no-strings-attached grants for "building a more just, verdant, and peaceful world"

-

Andy Matuschak (@andy_matuschak) has written about his independent researcher career and his experience being a Patreon funded researcher; Andy views his setup as a kind of a custom NSF CAREER grant

-

Nadia Eghbal (@nayafia) has done lots in this space, including writing about her independent researcher path and sharing her reflections on a re-imagined PhD

-

Nadia also set up her own fast micro-grant scheme, Helium Grants (2017-2019), and curates a nice list of grant schemes of different sizes, including grants for sectoral and regional projects, fellowships, and more, backed by both public and private institutions and more informal collectives; see also Nadia's Lemonade Stand

"I think there's a shortage of funding available for people doing cool stuff, which is silly when you consider how many people have disposable income today who want to support others' work, and how easy it is to find each other on the internet. There is no patronage equivalent to angel investing!"

-

Nadia's grants inspired others to run their own campaigns

-

Abe Tusk (@abetusk) ran a personally curated $100 microgrant program for free/libre digital commons content

-

Scott Alexander (of Slate Star Codex and Astral Codex Ten) runs the ACX grant scheme, supporting a variety of individuals; Scott recently announced a batch of awardees

-

In the same post, Scott Alexander also mentioned several other funding avenues, such as the Effective Altruism funds family, which includes the Long-Term Future Fund that seeks to "positively influence the long-term trajectory of civilization"; the post also has some discussion on networking and other non-financial resources

-

microgrants.net supports education, small businesses, and transportation through microgrants

-

Activate Fellowships — for scientists who are keen to "bring research to market as a new product or business that can benefit society"

-

Awesome Foundation — a lightweight umbrella org for a chapter model microgrant system

-

Indie Fund — an investment syndicate, a virtual Dragon's Den, for indie game development

-

Open Humans grant — grants to advance the Open Humans community, built around personal data and its uses in education, health, and research

-

Epic MegaGrants — $100M pot for "doing amazing things with Unreal Engine or enhancing open-source capabilities for the 3D graphics community"

-

For balance, the other leading 3D engine Unity has a social impact grant program called Unity for Humanity — not to be confused with the Unity fund for UK LGBT organisations

-

Many major open source software systems have their own development fund, Blender is a great example

-

Google funds newbie open source software work through the Summer of Code initiative

Others

-

The Open Collective Foundation is a "fiscal sponsor", a kind of a financial umbrella organisation for charitable initiatives; they support charitable grantmaking (h/t @natehn_)

-

GrantNav 360 — UK Gov run site for tracking grants issued by government bodies, private entities, institutions, foundations, trusts, etc., with a wealth of open data; mainly funding from institutions to institutions — recipient organisations can then run their own microgrant programs

-

Overedge Catalogue by Samuel Arbesman (arbesman.net) — a curated list of modern research organisations and related institutions

Wider landscape

-

Academic research, the primary domain of research universities and sectoral research institutions, is often funded by a mixture of public and private funds; the UKRI coordinates government funding schemes in the UK; the National Science Foundation is a major research funding agency in the US

-

Corporate research used to have substantial primary research element to it, but in modern times mostly refers to research and development (R&D) done in pursuit of new products and services

-

Artist-in-residence programs are a common way for institutions to support artists, often in the form of a studio/lodging/space arrangement and a peer community or other assistance; for example, The Point, Eastleigh, powered by Arts Council England, runs Associate Artist and @Home Artist programmes for performing arts groups; Whitechapel Gallery runs a writer in residence program, inviting people to explore "how writing is experienced through the lens of contemporary art"

-

Business ventures can be supported in a variety of ways ranging from bootstrapping via personal savings all the way to venture capital investment; there are business incubator schemes, equity pools (for "friends, fools, and family"), angel investors, business loans issued by commercial banks, national and regional business funding schemes, etc.

-

Universal basic income (UBI) and other public direct no-strings funding schemes have been talked about for decades; with the rise of the gig economy precariat and widespread yearning for self-directed work and varied careers, these proposals have gained support and currency in recent years

Challenges and Opportunities

This section is my take on Moths Minds: what it could be, and what challenges and opportunities may lie ahead. I'll pick up a few points from Mielke's announcement tweet chain and the Hacker News discussion that followed, and use them to explore the platform design space a little.

Language

There's lots of imprecise language in this space that may be causing unnecessary overhead and inefficiencies.

It would be great to see a richer vocabulary emerge to drive small-scale grant funding efforts forward. On the other hand, flexible language makes it possible to innovate within the broader grant ecosystem itself, as more things can be linked to it.

In any case, platforms have the power to establish a common language for talking about things, and that can lubricate certain processes.

Some examples:

-

Is it a grant or a gift or an award or a stipend/honorarium, or payment ex gratia, or a tip, or a donation?

-

Is there a difference between a one-off thing and recurring setups? Do we subscribe, as on Twitch and YouTube, or do we join as a Patron as in Patreon? Or am I making a donation?

-

What makes a grant a microgrant, or a minigrant? To whom is a sum large or small?

-

Are grants only for a specific purpose? Do we use a different word if the setup is more open-ended?

-

How do I signal my intention with words, if I don't care about how the grant is used? Can we do better than "no strings attached"? What if I have lots of "strings" to attach? Is there a continuum and a way to articulate how far along it the grant sits?

-

What kind of a project or work is worthy of a grant? What is research in this context? Are we doing science?

-

If it's an investment, does somebody expect a return, and if so, in what form?

-

Are funds the things that distribute grants or the grant itself?

-

If there's a specific deliverable, is it research or freelancing or consulting? Does it matter?

-

Does a grantee have a donor, or a recipient a funder, or what?

-

Does anything change about the language if the recipient is an individual, a team, an organisation, an institution? And how is it with the sending end?

-

Who am I if I support Moths? A mothkeeper? A bulb? Just another Moth?

-

Who am I if I both give and receive?

-

What does indie/independent mean — do I have to work alone? Can I be affiliated with an institution and just do this other thing as a side gig? What if I do my best work as part of a squad?

Standards and Defaults

The greatest service that any platform can do for the world is to establish a standard with sensible defaults.

Regardless of what happens with the platform, the standard will leave behind a baseline, a benchmark, a norm — something on top of which those that come later can build on. If Moth Minds is about playing the long game, bringing positive change to world, setting a standard for independent research grants could be a huge thing for the whole ecosystem.

To appreciate this, consider an example in the adjacent domain: because GitHub prompts for a README, a .gitignore, and a licence when creating a new repository, authors are invited to think about these things on day 1 of their experiment. One little nudge can have profound consequences.

And defaults matter. If Moth Minds takes over the world and creates a standard grant that is default open — open data, open publishing, open reporting, Creative Commons, etc. — everything that comes after has to argue with the marketplace of ideas in order to do things differently. And it's hard to argue against openness once that has been normalised. At the same time it's "just" a default: there's no limitation with respect to other approaches.

In the same way I would also advocate for finiteness in everything. The Patreon model, subscription schemes, is popular with all kinds of online services these days. Unbounded support works in some cases, but grants probably isn't one of those. Grants should be finite in time, in budget and other resources. Setting boundaries fixes a scope and helps with planning: the constraints set the artist free.

The DARPA model, everybody on a fixed term contract and so on, is worth emulating today. Recent UK Parliament inquiry into what will become the ARIA research funding body has lots of good discussion on DARPA and research funding in general. I also recommend the early 2020 report on a "UK ARPA" from Policy Exchange, a UK think tank, called Visions of ARPA (pdf). Everybody doing research funding should know about the Heilmeier Catechism.

Pursuing standardisation can also provide an early roadmap for the Moth Minds mission. A good first thing to aim for could be a template for personal funding agreements. Setting the standard for documents and patterns could really propel the whole personal grants scene forward.

For precedent, look no further than YCombinator and their SAFE document suite for early-stage fundraising. Build something like that for personal grants and bake in openness and so on. Reasonable intellectual property clauses is another thing one would absolutely want to get for free with a standard grant agreement. At the very least, the IP stuff is a prompt to make sure that the IP conversation is had at some point early on.

As I understand it, SAFEs were a huge lubricator for the Silicon Valley startup ecosystem. SeedLegals and others eventually adapted SAFEs for Europe as well. Establishing something like a SAFE for personal grants could be a massive thing: an early feather on the Moth Minds cap and a huge press opportunity, legitimising the whole thing.

Finally, how could one go about building such documents and things? One could always try to crowdsource it via GitHub or a similar setup. The starting point should probably be a mixture of existing grant schemes, with feedback from people who have had personal grants. Bash those together in an RFC type of thing and find someone to drive it. Submissions, edits, and point of discussion via pull requests.

Clearly what is needed is a meta-grant to persuade somebody to put the necessary initial effort into this.

The Marketplace

If the Moth Minds platform was a marketplace, how would it function? Several dimensions to consider. I'll pick three central ones to begin with: dynamics, discovery, and the invisible hand.

Dynamics

One of the main things to get right in the early days a of a platform is the dynamics, the rules of the game.

For Moth Minds, the question is: Who funds whom? It's a different vibe if it's one person funding many (1-N), several people coming together to support an individual (M-1), or a free-flow multi-party setup (M-N). The dynamics at play influence the way communities form on the platform.

A flexible platform could probably grow to eventually support all of these types, even innovate in each one separately. This leads to the even more fundamental question: What does the platform actually do, where's the value? How exactly will Moth Minds support each of these grant schemes, if it supports them at all? (1-N, M-1, M-N)

Or is the platform there for you at an even earlier step? Moth Minds as the platform where a prospective grant provider can resolve this question? Or much later: Is MM just a grant flavoured dressing on top of some Stripe-like processor? What is the hard part to solve for here?

Dynamics leads to relationships. 1-N usually means standardised reporting, where there may be some compatibility issues between the nature of the work being done by the grant recipients, and what the sole grant provider can handle on their end. Some providers will be happy to fire and forget, others have their own reporting to see to.

M-1 is the subscriber update model where the sole beneficiary is beholden to a bunch of strangers on the Internet. Not all can handle having a hundred anonymous minibosses asking the same question about admin trivia. The social overhead can be substantial, especially for those who just wish to do research, say. The platform can do a lot here to help everybody out, to manage expectations, etc.

M-N then is a forum of unequal partners, a free-for-all. Again, the platform can support ways of bringing order to it all, but this is just fundamentally messy. Perhaps benefactors and beneficiaries can form their own peer communities or clubs within a club. I would lean on the previously mentioned collective or squad notions — e.g., having an option for grant recipients to only report to collectives, not individual backers.

People will also try to game the system, life will happen. Dynamics and relationships — people being people — means the platform will eventually have to have measures for dealing with all kinds of people issues. On the other hand, reputation goes a long way and people often bring their own established communities with them.

Discovery

The second marketplace dimension to consider is discovery. Discovery is the process by which supply meets demand.

A grant marketplace is a clearinghouse for ideas. The key market activity is connecting people, connecting the right funds with the right ideas. In crowdfunding there's a natural mechanism for this: the crowd either funds your project or it doesn't. Individuals make mostly independent decisions about their engagement. Often it all reduces into a popularity contest, where the successful ones win visibility and attention, which yields more success, and so on.

In other words, discovery is a function of popularity. Platforms may work with or against popularity, and even say one thing and do another, as with Roblox. Additionally, platforms can help users engage with the wider marketplace, the more/less popular corners with functionality such as search, categorisation, discounts, matching, etc. Effective market discovery on the web is far from a trivial problem, but there is a fairly well-established playbook for it.

Moth Minds has a unique opportunity to go a bit further due to the nature of the "product" on the marketplace.

Research funding is a matching game where the fund provider has a target sector (or even an agenda) and the recipient has a certain focus area. It's all about the overlap. In normal markets vendors put up their wares and customers pick up what they like. Take it or leave it. But when the "product" is as immaterial as research and ideas, the interaction can be more conversational and vibrant — a negotiation.

Imagine if the platform could help researchers focus their efforts in areas that the market finds interesting. There will always be people who know exactly what they want to do, and those with highly specific ideas tend to find what they seek in any marketplace. Or they'll fail, scrap their idea and move on to the next definitive thing. But there are also people who would be interested in things in a certain broader area.

Public funding works by call for proposal schemes (CFP), where researchers are invited to submit detailed research plans with expected outcomes. This is guaranteed to not result in anything radical. Maximal gatekeeping.

But consider a different approach where the platform could support a kind of a staged grant shaping process. Imagine a scenario where a funder could first propose a moderately broad grant target area, and the market — hungry researchers — could then help direct and narrow it down somehow. This could then be iterated on until somebody makes a detailed enough, fundable proposal within that narrowed scope. It's a search for the sweet spot between an individual's and the funder's interests.

One could even have a crowdsourcing element at every step: "I'd like something like this to be funded, even if I'm not awarded to do the work", etc.

Obviously purists would bridle at such an invasion of their independence, such interference with their vision, but the idea is that an effective marketplace is a space where reasonable people can find a mutually beneficial compromise. The market shapes players both ways. Or, to put it another way, I'm talking about an immediate grant-meets-research feedback mechanism operating through the call for proposals process.

True discovery means discovery at every level, meaning that there's room for those with a clear idea in their head as well as those who have merely the vaguest inklings. The market decides which ideas get to live. Sometimes you only need to convince one person.

Patreon and Kickstarter and all the others are yes/no. Either you support or you don't. There are no other ways of contributing. But surely there's room for innovation here. For example, what if people could argue for the kinds of grants they would like to see?

Invisible Hand

This multi-player grant provision discussion brings me to the invisible hand, Adam Smith's famous economics concept that has been abused for over 250 years now.

Roughly speaking the hand refers to the idea that entities acting in their own self-interest may bring about beneficial change in the wider sphere beyond their own person. At the aggregate level of a market/economy/society the effect is as if some invisible hand of providence guided individuals' actions to maintain order for the benefit of all. This line of reasoning was later developed into a broader theory of externalities.

In her Moth Minds essay, Mielke states that her goal for the platform is to "catalyze more interesting, future-forward projects in the world" and to "collectively raise the baseline level of agency in adults". Moth Minds, if successful, would be much like an invisible hand in the grant marketplace, with everybody benefiting from a supportive atmosphere where individual success stories motivate others to pursue their own dreams.

Indeed, with grants it's all about the externalities. If there is no impact beyond the person who received the grant, regardless of what they did with it, in many cases it would be reasonable to say that the grant was misallocated. The grant could equally have gone to somebody else, some other project with more impact. On the other hand, it isn't reasonable to expect a great return from all investments. Trying things out is risky and grants should support such activity. Evaluating externalities is a challenge and the feedback signal is difficult to shape.

Further, the free market, by itself, often does not lead to the best outcome overall. Joseph Stiglitz argues that whenever there are externalities, markets themselves will not work well. Some regulation is required to make markets work. The task is to find the right balance.

So I guess this is a warning. If the Moth Minds grant platform becomes a marketplace in any sense, one should be mindful of the incentives of the market participants, the metrics of evaluation before and after a grant, and of the positive and negative externalities generated by the grant programs. It's good to think about the levers of regulation and control that funders have and the levers available to the platform. Especially if building communities is the goal.

It's also worth remembering that only dead ecosystems have no parasites.

Community

An online community is just people being people at each other — at scale. For better or worse, the people are the platform. Some thoughts on early adopters, the selection problem, network effects, and other mixed blessings.

Early Adopters

Most early interest in the Moth Minds scheme will likely come from people who wish to be on the receiving end of whatever grant schemes emerge from the platform.

While that's the whole point in a way, it would be wise to not let this signal be the only guide in the development of this idea. A true platform has at least as good a story for the supply side as it has for the demand.

In the Hacker News thread, many viewed Moth Minds as (just) another potential avenue for funding open source software development efforts — no surprises there. Many readers dreamed of quitting their day job and leaving behind all the meetings and the managers. Just solo open source hacking all day, every day, and a faceless benefactor there to settle your bills. This is a great example of a one-sided view that is worth actively challenging.

Or, who knows, maybe there really is a vast pool of open source funders out there, completely underserved by all the existing platforms. It doesn't seem all that likely. And yet, toy projects and communities of software tinkerers around them might be exactly the sort of thing that Mielke is trying to incentivise with her platform.

As far as I can tell, Moth Minds will be oriented around individuals supporting individuals. I would leave the door open for institutions supporting individuals as well. And then there's the exciting option of having loose collectives support individuals.

Aside: A Patreon group might sometimes reasonably be called a community, but I wouldn't call a per-project Kickstarter backer set even that. There's more to a community than a shared message board to commiserate on. And there's definitely way more to a collective than there is to a community. This is all about shared agency, remember?

To be clear, by a collective I mean a group of people coming together to fund grants as a single entity, under one charter or what have you, to the tune of the Awesome Foundation or even "Squad Wealth".

The mini option, individuals supporting individuals, a kind of a project-oriented/one-off Patreon or research Kickstarter-lite, is an interesting direction, but I wouldn't start there. Having a platform that can both handle M-N flows AND support community building on top of it is quite a task, quite a build.

I would look to institutions and collectives first. Institutions should be able to articulate what they need in order to participate, and should be able to provide feedback on what they'd like to see. Furthermore, winning "business" from even one major donor is a huge signal to others that the platform is a legit thing. One major donor can bring the whole platform alive by supporting multiple projects. In short, starting with 1-N grant setups is easier.

That said, the collective grant direction would be particularly interesting, because there's barely any precedent, and a platform for that could really launch the community side of Moth Minds. Again, one might start with a 1-N setup, maybe a "house squad" grant scheme, or one where launch partner individuals put up the first grants together. This first batch could then set the tone for the whole platform.

The Flame That Burns

"Nice, can't wait to be owned by strangers"

Hacker News was quick to pick up the Moth Minds announcement, with the resulting debate being quite sharp, as usual. The main point of contention in many threads was the selection process. By what mechanism do the grant givers sort out the wheat from the chaff? Who are these moths? Why should one be funded over another?

If Moth Minds cannot support the grant supply side — or ideally both sides — in the grantee selection process, the whole platform reduces to a thin veneer on top of a payment processing system. Which may be fine: just people funding their friends and acquaintances. But that would be a missed opportunity to build something greater.

If the process for getting selected for a grant is too onerous or unwieldy for everybody involved, the moth platform might just serve butterflies after all. It has to be smooth.

On the other hand, if it's all open and communal and generous, the platform will quickly become saturated by scammers, fraud, waste, and noise from the delusional. The end state will be some form of tragedy of the commons. Then again, if the platform provides overpowered programme steering controls, or there's some other strong built-in filtering mechanism, one ends up with a rather brutal platform where only the fittest survive.

How does one draw a line between moderation and gatekeeping? What are the boundary constraints?

User @nickff argues the adverse selection issue. User @webmaven offers grant funding lotteries as a potential solution. Both perhaps are overlooking the charitable dimension of it. Some grant providers may not even require a tangible "return", though of course one always wishes to allocate resources effectively. User @13145 suggests progress tracking and expectation management as alternatives to filter-first social Darwinism.

"[If] you expect a measurable outcome from small-scale investing in people then don't do it, you're in the wrong space. If you view your investment as a path to the outcome you have in mind for them then don't do it, you're in the wrong space.

If you believe that a person deserves opportunity that might otherwise be blocked from them by what the privileged of us would consider incredibly low bars (money) and are willing to possibly not ever know if it made a difference or where that took them then it might be for you."

It's a tricky balance to hit, because there's subtle human behaviour weighing on both sides. The positive ethos at the heart of the Moth Minds initiative may face a stiff reality test, when it opens the doors to the big bad Internet. And yet, the unpredictability of it all is the source of the platforms greatest potential.

Balance means that not everything will be successful. Should failure then be the expectation for grant programmes, as with startups? What does that even mean? And what is the social cost of public failure? Is there public feedback?

One on hand, the world does not owe anything to anybody. Certainly nobody is entitled to have their hobby funded by others' generosity. There will always be more demand for grants funding than there are resources available. Filtering will happen: some will win over others, it will be a competition.

For some, the filter is a useful feature, a method for sussing out the worthy, that wheat from the chaff, the signal from the noise. For others, filters are something to minimise, so the recipient pool and potential impact can be as wide and unconstrained as possible.

Grant providers will be the parties that decide how the game is played. The platform would do well to support them in this. There's definitely plenty of room for innovation. One could, for example, explore lottery mechanics to blunt the competitive side of grant proposal games. And there's bound to be more to explore in the direction of quadratic funding and community engagement. Maybe there's a way to do collective program moderation in a way that avoids both trolls and the negatives of gatekeeping.

"Tech's biggest opp in next 5-10 years is building cultural institutions in its name. A lot of this work will fall outside of tech's core competency w/ startups. We're in the "pickaxes" stage of building for the future."

Consequences

If the grant recipient has nothing to show for their project at the end of its life, what consequences should there be?

On one hand, it would obviously be good to have a mechanism that curbs dishonest or fraudulent behaviour. At the same time, life happens and things don't always go to plan. Projects and people just fail. Grant providers certainly shouldn't try to claw anything back, but on the other hand, we are talking about individuals doing the benefaction. It would be good to have mechanisms to acknowledge their "loss" as it were, a dignified way to say that you grant failed, but that's okay: Would you like to try again?

When it comes to failure and failing, one can trust communities and their ability to define and enforce norms and policies. Those who are able to deliver good stuff, who respond well to grant funding, should be elevated and have greater opportunities and influence. At the same time, there should be mechanisms to encourage newbies. Collectives, mentorship schemes, etc., could help here.

As a grant recipient, if you don't deliver — and even failed programmes should have something coming out of the other end — you probably should lose some of your standing on the platform. The marketplace handles much of this automatically, people vote with their wallet, but there's more to it. If you don't deliver, your whole platform identity should not be destroyed. We should all have second chances and third chances and more. We want to encourage experimenting and failing gracefully.

If a grant recipient doesn't hold their end of an agreement, the right resolution is to have more carrots go to other people from the next batch. Unless there's serious failings somewhere along the way, serving stick to this one individual doesn't accomplish much.

Ideally, there would be a way for disgraced makers to join and re-join collectives first in a small capacity and then build from there. If individuals are willing to put in the extra effort to win back trust, they should have a clear path forward. Reputation is a fickle thing, but it should always be possible for you to get your act together, as it were.

Obviously funding providers need to play nicely as well. With providers, I'd say the risk of misunderstanding and miscommunication is far greater than that of malicious behaviour. But again, life happens.

Network Effects

User @ssalazar asks in the HN thread whether Moth Minds could be an alternative to venture capital: a way to lure inspired individuals away from their comfortable butterfly day jobs to work on something they believe in, but without the overhead of running a company. Indeed, venture capital supports only high growth potential ideas, which is a strict subset of all bright ideas. Moth Minds could target ventures that aren't attractive enough for venture capital and also not flashy enough for Patreon/Kickstarter style mass appeal.

Without commercial pressure, as part of a community, perhaps great work can more easily be done in the open.

User @benfahraman advocates for peer structures and mentorship in his Moth Minds commentary. Indeed, research and other solo gigs can be quite lonesome activities, especially for those just getting started in this way of working. Going at it alone is ideal for certain types of work, but from time to time it is good to get feedback and bounce things off a real person. Perspective is what you lose, when you're ears deep in the thing. The platform could host tooling for optional progress tracking, reporting, catch-ups — though others would not want anything of the sort.

Scott Alexander recently reported that the opportunity to be part of a network was appealing to many in the grant pool. If the Moth Minds platform had lightweight mechanisms for mentorship activities and peer link building, that could be a huge boost and a meaningful feature for many. Related admin needs good tooling as well.

One can imagine a kind of a mentor marketplace, where those who are starting with a grant can match up with those who are interested in keeping tabs on a particular field through mentoring. Perhaps every Moth needs a way of saying what they would like to work on and what kind of work they would like to support.

Or maybe we need more nemesis energy.

In any case, the community side of the platform could prove to be one of those massive things. What better way to promote moth-ful agency than sharing your work with a receptive community?

"The most beautiful part of the internet is meeting your people."

Old Innovators

Moth Minds is focused on individuals, but there's no reason to completely ignore existing institutions.

Corporate Innovation

When companies grow up, they tend to lose their sense of adventure. Processes, products, and people all settle in their grooves. Rapid growth and radical change make way for a more stable and incremental way of getting on with the business. Individuals come and go. What remains after a decade or ten is mostly just a memory of the great early years, when everything was dynamic and exciting and new.

In a way this is inevitable, and even a natural part of corporate evolution. Nothing lasts forever. On the other hand, companies are made of people, so in theory companies should be able to renew themselves with every passing cohort of colleagues. In reality there's always something about institutions, the commercial inertia of it all, that makes it difficult for companies to reinvent themselves.

The world never stops changing, so companies do have to respond in some way. Quite often established companies seek advice from management consultants who can talk freely about the outside world. They may have suggestions on how to re-position the business to make the most out of current opportunities. Other kinds of consultants can also make appearances at the company, bringing news and new ideas, new practices.

Another thing mature companies try to do is to embrace change through internal processes, from the inside out. There's always some kind of an innovation initiative underway, a kind of a corporate mid-life crisis.

These established, habituated companies could be an interesting target market for grant programs.

Imagine companies taking a slice of their innovation budget and putting it towards a custom grant. The idea being that the grant recipient is almost like an independent consultant providing a service, but it could well be structured to be more open-ended, without a specific deliverable. The grant could serve both as a catalyst for reactions inside the company, as well as a recruitment/marketing probe. The funds are definitely there — it's a question of how to unlock them in a way that is beneficial for all parties.

The challenge is that companies typically want — or believe they want — innovation with a specific kind of pre-determined output or result. This kind of well-behaved beast is pretty much a contradiction in terms. In other words, there's an opportunity, or even a requirement, to offer grant issuance guidance. On the other hand, highly focused missions could be relatively easy to finance. Companies have expertise on procurement.

Of course, there are some interesting fundamental questions to consider. Why should company X invest in a random person Y outside the company? How can Y work publicly on something that is of value to X? What is the value for X in this case? Is it always dependent on the company, or are there universals? Is good PR/visibility/HR boost enough?

Regional Players

I was recently in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to see the postponed Dubai World Expo 2020, the first exhibition of its kind in the Middle East. The expo, quite a complicated institution, is a very different creature compared to the legendary ones of previous centuries, but the happening still managed to capture my imagination.

One of the things that struck me at this expo was how keen all the countries were about putting their innovation foot forward. Everybody wants to invest in innovation and be seen as the most dynamic of places, as the urban garden where the future is invented one startup at a time. Every country wants to be the hub where people come together to have a great life and create a better world.

The UAE itself is no exception, of course. All of the oil rich countries are keen to build infrastructure and impressive buildings, but investing in innovation is a whole different level of ambition. It's an easy sell is what I'm saying.

Moth Minds is about individuals, but just as an exercise, just as with corporations, consider how national players could contribute something to the platform. Every country has an innovation fund of some kind, and these funds run all kinds of pilot programs. If there was a global platform for these efforts, maybe something new could emerge from that. At the very least, this could be a way to introduce these innovation funds to a broader audience.

As with institutions, you'd only need one pioneer to lead the way and you'd get a dozen copycats immediately.

The key thing would obviously be regional targeting, or perhaps an invitation to do the work in the target country or even a particular local community. Personally, I believe in cities: the global city will be the fountain of agency that makes major things happen in the real world in 2050.

Giving and Grantmaking

Mielke invites smoke signals from potential Moth Minds donors with a nice little form on her site. Just a name, email address, "type of work you'd like to fund", and a rough estimate of the total grant sum you could be interested in providing. The suggested funding categories are 1-5K, 5-20K, 20-50K, and 50k+.

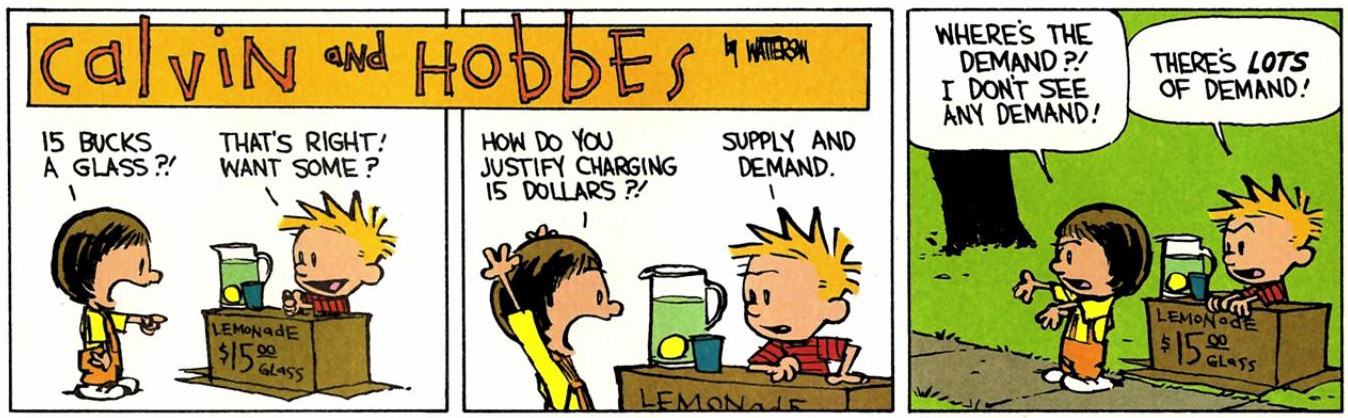

The complete disregard for currency symbols is one thing, but the whole approach is endearing. It's a charming effort brimming with good intentions and innocence. And yet there's that ambition — or is it agency? A fine mixture of good old lemonade stand energy and some Silicon Valley chutzpah.

I don't think people willing to part from $50K for an experiment like this go around filling forms online, but then again, it never hurts to ask. Sometimes people just...want to give. And, yes, this is on-brand for the whole mission.

Scenarios

I'll conclude this piece with some thoughts on what kind of giving and grantmaking I could see myself engaged in.

Let's consider a some scenarios. I think of the following as levels of engagement at which I can see myself contributing to some kind of a grant effort. The exact numbers are not essential, this is more about tracing out a curve or a continuum. The point is that there are thresholds where something changes.

Scenario 0 — Charitable giving

This is in a way the baseline. If I follow the advice from HN user @weego and make a bet where I'm "willing to possibly not ever know if it made a difference" and where I'm okay with not knowing where the grant takes the recipient, then the amount doesn't really matter. I call this charitable giving.

If I give £10 as one-off thing, that may or may not have an impact on anything. If I give £1,000 on a monthly basic, same thing. We're talking about a fully hands-off sort of thing here.

Many people will happily split a personal £100/month charity budget into a hundred little streams and sponsor in a tiny way a hundred projects they have some personal relationship with. There is no expectation of return, except for the projects' continued existence.

If there's an outcome that I can read about or otherwise enjoy, I'll be mildly interested in checking it out. If my small contribution was used effectively and it did in fact make a difference, I might be persuaded to part from more of my money in the future. Conversely, if my contribution doesn't seem to have any impact, I'd have no qualms about reducing or ending my support for a any particular mission.

For charitable giving, I suppose I would be willing to do some of the recipient choosing/selecting/vetting myself, but the smaller the small sum, the less involved I'd wish to be in the selection of particular recipients. For every level, I feel like I'd prefer to support a cause or a theme — a squad, an institution, a movement — and thereby trust someone else to allocate my contribution for me. I can see this being a crowdsourced / democratic function as well.

I know others wish to be more hands-on, and want to "do their own research" about recipients and so on. But for me, I'd be happy to chip in a small amount for a one-off project grant fund if the idea sounds good. Ideal case is that there's a specific thing that some people want to do and my contribution is one of many to help realise that. This is how many of the current platforms work.

I'd strongly prefer to make a one-off contribution over a commitment over many months. If I have control over my contributions month after month, I'm compelled to make use of that control.

Scenario 1a — £10/month, a subscription

Let's consider ways of giving where I'm more invested beyond a fire-and-forget charitable donation. First up is the Patreon model: small monthly recurring contributions, with promises of something in return.

For context, $10 per month gets you a Netflix subscription. This is not a large sum of money for most people in my area. The minimum wage in the UK will be £9.50 from April 2022, so this can be seen as the equivalent of an hour's worth of effort per month. £10 goes a long way on Fiverr.

If such a grant is taken to be a transactional agreement between two people, I would expect to get regular updates featuring something that took about an hour to make. One every month. Maybe a sketch, a short composition, a short piece of writing, a nice poem, an insightful review, an increasingly good demo to play with.

£10 is not much of a grant on its own, but if it's one of many in a pool, then the aggregate may become worthwhile for the awardee. If you have 10 patrons of this kind, you can spend 10x that one hour on something, and then share that more substantial thing with everybody. Each of the 10 supporters get to enjoy a thing that took 10 hours to make. And maybe it is made public afterwards.

This is the essence of the Patreon model: regular content, a little exclusivity, and early access as thanks for recurring support. Every month someone receives my £10, and I get a piece of something from them in return.

Scenario 1b — £120/year, a lump sum

If the £10/month is all rolled up into a lump sum that I contribute to one or two projects annually on average, we get the Kickstarter model. The Kickstarter mechanism where some critical mass has to be reached before anything is allocated, works nicely with individual lump sum contributions.

With Kickstarter, as a supporter, you also know exactly what you'll be getting, if everything goes to plan. I don't think is necessary, but it does make sense in some cases.

The lump sum model is particularly great when the money is needed upfront, all at once. For example, one might need to buy equipment or services, etc. Trickle feeding is a real limitation of the Patreon model. On the other hand, equipment can often be leased on a monthly fee basis and so on. In any case, with lump sums I expect more definition and polish in the proposal: a Patreon pitch is by necessity more speculative and focused on potential and the general direction and orientation.

Intermission: Collectives

For more open-ended support, I feel like I would rather support a collective with a theme rather than choosing a particular individual. I imagine this would start with something like a catalogue of collectives or themes, where I could browse by topic and then quickly scan the contributing members of the squad behind the proposal.

Let's say I come across a squad of five people excited about 1950s science fiction and they have plan for a short film or other media in that tradition. I can then evaluate their proposal material and make a decision that okay, this year this is the squad I'd like to support with my £120.

If the collective has a hundred benefactors like me and the pot is balanced out, that's £200 per head, per month. Not a great sum in the grand scheme of things, but maybe enough for people to put some effort into their passion. With a thousand-strong collective, £10,000 to go around every month, that could be enough to incentivise people to really make something great.

The point of the collective is to abstract the relationship, both ways. On the receiving end of patronage, maybe you cannot contribute to the project every month: the abstraction allows you to skip that month, with the pot of the month going to those that do contribute. No pressure to perform, or at least the pressure is of a different sort. If there's NO pressure to deliver anything, then we are veering off the Kickstarter model towards charity. This may be perfectly fine in some cases. On the other hand, the squad will police itself.

The other benefit of a squad approach is load balancing. If I "subscribe" to a collective, I primarily support the theme or topic of that group. For example, let's say there's a band of "tools for thought" researchers. Maybe you have prototype cooking that takes three months build, and so your squad mates cover you for two months until you are ready to show your thing. And yet, every month I get to play around with something or get a review of developments in the scene or something. With individuals this isn't possible: either you don't have an update, or you scrape together something small-time every month, which is not great for anybody.

Scenario 2a — £100/month, multiple subscriptions

If I increase my budget tenfold, the basic idea stays the same. I can either give the same £10 to more projects every month, or make a larger investment to fewer projects. A platform like OpenCollective could work here.

£100 per month is still a relatively small amount, though certainly not for everybody in my area. £100 per month is enough for multiple streaming services AND several newspapers and magazines. I could get lots of content for £100, or commission something a bit more involved or higher end.

If the number of recipients grows, my disposition towards each individual recipient probably changes. Do I want 10 updates every month? Maybe, I'm not sure. What I do know is that I don't really want to "manage a portfolio" or do anything of that sort on a monthly basis. I don't want to spend time every month curating a list of people whom I deem worthy of my continued support. Maybe once a year I can adjust my allocations, think about themes for the upcoming year or take stock of what people have done with my contributions.

At this scale, the idea of supporting a collective instead of individuals directly continues to make more sense to me. With additional investment, I generally wish to incentivise the production of better stuff, not simply more stuff.

Scenario 2b — £1,200/year, a heavier lump sum

£1,200 as a lump sum is large enough of an investment that I would want to be more deliberate about its allocation.

If the lump sum is divided over ten recipients, the process would be much like the £120/year case, just with more effort for me to find and select those ten. I'd still be happy to fire and forget. Here, the portfolio idea makes sense: I "invest" in ten projects and hope that some of them result in a positive dent in the world in the next 12 months. If I have a good experience, I can see myself investing more, or re-investing in the same people. Otherwise I move on to support other things.

At this level I would still strongly prefer to support specific projects with a finite scope, rather than investing in individuals in an open-ended manner.

On the other hand, £1,200 is starting to reach a level where it could be large enough for a true personal grant, a setup where I am the only benefactor. It is my grant, given for a specific purpose, so I should probably be more involved and vested in the selection process. On the other hand, £1,200 is still within a range where I could see myself fully delegating the selection to an entity that can make a much more informed selection choice.

For example, if there's a pool aiming to raise £10,000 for a particular grant, I'd be open to contributing my whole annual lump sum of £1,200 towards that. Though that would require a mission that I really believe in. I would also be interested in voting on proposals or participating in the selection process in other ways.

Scenario 3 — £12K/year, a grant or grants

£12,000 per year is a good chunk of money. A £1,000/month is enough for basic room and board anywhere in the world. Maybe not a great space, but one should be able to figure something out on such an income. The UK basic State Pension is about £600 per month, and job seekers get an allowance of roughly half of that.

£12,000 is large enough of a sum that most people in my area will never have that much in disposable funds. However, there may be circumstances in which such an option becomes possible.

With £12K and beyond, monthly giving schemes feel a little disingenuous. I would not want to to support a hundred projects with £10 each and then dive into their updates. I would not want to do the monthly maintenance on my "portfolio". I could put £100 towards ten projects per month, but ten £1,200 annual lump grants seems more effective somehow. I can see each £1,200 going into a larger pot, as before, or be a standalone thing. I could also make larger individual contributions, but really at this level we are in proper grant territory.

This whole piece is my attempt to figure out my views on grants, so I won't go on much further here. In a nutshell, what I'd like to see on the platform is a way for me to both A) solicit proposals in a particular area that I'd like to see activity in, and B) browse a catalogue of ideas in which people would like to be active in. If I want to invite research in my favourite subject, I can either set up a minigrant to that effect and carefully study the incoming proposals, OR I can find existing projects/ideas that people have and then approach this individual or that squad about a project in that space.

I could do this at all multiples of £1,200/year, in lump sums. I'd like for the platform to have tooling for managing the allocation itself, but also for everything that goes on around it. The platform needs good mechanisms for idea and people discovery, for proposal vetting, for feedback and reputation things, for reporting, and so on. I'd like that all grant related communication goes through the platform, at least initially.

Theme Sponsorship

To round things off, let me illustrate the idea of theme-based personal grant sponsorship.

I'll choose "Computing in society" as my theme. Under this umbrella I can then invite project proposals, as well as propose topics myself, in case I can inspire somebody to work on things in this space.

I'd be interested in supporting any of the following strands with my own "Fringeling Grant", in no particular order:

-

The history of business intelligence: definitive timeline, main developments — would be wonderful to have a nice, up-to-date book on this, or an interactive website or something

-

Research towards and prototypes that try to realise aspects of Bret Victor's Seeing Spaces ; I'll settle for a Dynamicland branch / Realtalk house in my local area

-

An in-depth biography of Alan Kay, covering his work from decades ago, but also distilling his more recent views and lecture materials, etc., into a nice "companion"; in fact, such "companion" books on the work of other computing pioneers would be grand as well

-

Live coding culture in my local area, particularly events

-

Julia Koans — inspired efforts to create Ruby Koans for Julia

-

A computing themed escape room

-

Computational art projects

I think I would also be open to supporting the development of the Moth Minds platform and/or community by contributing to a MM development grant pool.

Summary

Moth Minds is an upcoming platform for grant programs. The introductory essay captures my imagination, but more details would be great, in particular a clear articulation of what the platform is and isn't, and how it compares to existing platforms.

A platform can be many things, but above all it presents an opportunity to shape an entire sphere of activity. Platforms make processes and interactions more efficient, add scale to operations, and help people and resources connect in powerful ways. A platform can establish standards and a common language, supporting shared understanding. Platforms are all about the user experience — on both the sending and the receiving end.

There are many crowdfunding platforms and even some focused on direct financial patronage. Many individuals and institutions have run their own grant programs over the years. There's certainly some tradition of personal patronage to draw on, when designing the mechanism for the Moth Minds platform.

The new platform will face many challenges, but equally there will be opportunities to re-imagine and to build something completely new. Some things to consider:

-

Language: There's lots of imprecise language in this space that may be causing unnecessary overhead and inefficiencies.

-

Standards: The greatest service that any platform can do for the world is to establish a standard with sensible defaults. An early emphasis on openness — open data, open publishing, open reporting, Creative Commons, etc. — could prove highly influential.

-

Market Dynamics: It's a different vibe if it's one person funding many (1-N), several people coming together to support an individual (M-1), or a free-flow multi-party setup (M-N). The dynamics at play influence the way communities form on the platform.

-

Market Discovery: A grant marketplace is a clearinghouse for ideas. Moth Minds has a unique opportunity to go a bit further than the standard online marketplace due to the nature of the "product" on the marketplace.

-

Invisible Hand: With grants it's all about the externalities. Everybody benefits from a supportive atmosphere where individual success stories motivate others to act.

-

Early Adopters: Most early interest in the platform will likely come from people who wish to be on the receiving end of grant schemes. It would be wise to ensure grant providers have at least as much influence on the mechanics of the platform.

-

Collectives: Having loose collectives support individuals could be even more exciting than having individuals support individuals bilaterally.

-

The Flame: There are many issues to tackle when it comes to platform operations, including filtering and the selection process, malicious behaviour, reputation, and how success and failure get handled. Great tooling is needed at every stage of the grant programme life cycle.

-

Network Effects: All platforms are made up of people, and people tend to be people at each other. Platforms generate complex crowd behaviours with real world consequences. The special relationships that are mentorship and nemesis-ship, could be relevant for the new platform.

-

Old Innovators: Institutions like corporations and regional public bodies could be interesting grant provider partners to work with. You'd only need one pioneer to lead the way and you'd get a dozen copycats immediately.

-

Levels of Engagement: Some people will want to run their own grant programs solo, others may be interested in contributing to a grant pool with a smaller donation. Some people will prefer monthly contributions, others will prefer one-off lump sums. Some people want to be highly involved, others fire and forget.

CODA: Mothology

"Moth Minds" is an interesting name for a mission, because there's a story behind it. However, I think the platform might benefit from a different name that somehow evokes the idea of catching the interest or attention of a moth.

Maybe not moths to a deadly flame, but more like that white sheet in the forest sort of business. What do you do when you want to catch moths? "Beacon funding"? "Candle funding"? Flame funding? Lumos? Bulb? Sheet light? Illuminati? Searchlight? Lightsearch? Enlightenment for moths?

Norm MacDonald, who recently passed away, had a wonderful moth joke in the good old shaggy dog tradition.

British eco-charity Butterfly Conservation informs me that here in the UK we have only about 60 species of butterflies, but over 2,500 species of moths. This is probably the main reason for why collecting butterflies is a thing: it's a smallish finite number to aim for. Each new one you catch represents a good percentage of the overall task.

Or, to spin it another way, when you meet a butterfly, you probably have met someone similar before, whereas a random moth encounter might be a whole new experience.